Reading time: 5 minutes

The trilogy is complete! The third paper from my PhD has been accepted. This paper observationally defines one of the oldest objects in astronomy – open clusters – while also producing the largest and most accurate catalogue ever of Milky Way star cluster radii and masses, using these to set new theoretical constraints on the overall star cluster population.

This blog post will go over the key findings and figures.

Context: our catalogue had a flaw

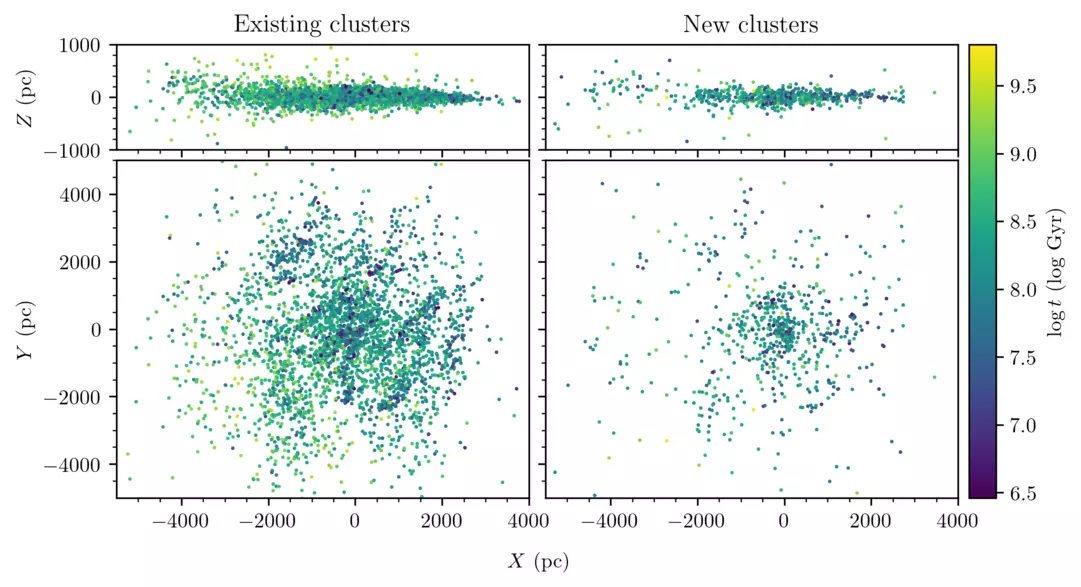

We detected thousands of clusters in our previous work. But looking at the distribution of existing (recovered) clusters and new clusters, it’s clear that most of the new clusters we found were near to the Sun:

Why is that? Did we just find >1000 new open clusters near to the Sun that had been missed previously? Or did we find something else?

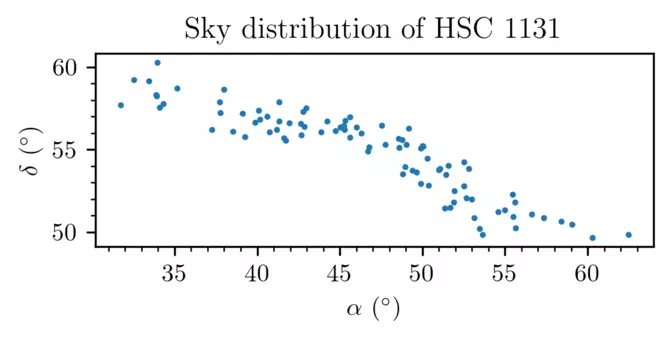

Looking at some of the new clusters near to the Sun, it’s clear many of them don’t have a ‘clumpy’ clustered distribution like the clusters in the header image of this blog:

This cluster looks a lot more like a stream of young stars that formed together. It’s really cool that we find them! But it’s also really annoying, because we needed a way to classify between these (presumably) unbound clusters and the bound open clusters we set out to find.

Radii and masses

After a lot of looking through theory and trying many things, I found a way to do this! We define a bound cluster as a cluster with a Jacobi radius (or Roche surface) within which its gravity is stronger than its host, the Milky Way galaxy. In principle, unbound groups should not have a Jacobi radius.

To measure this, you need the cluster’s mass as a function of radius, and some information about the strength of the Milky Way’s potential, which we queried from a common potential model. Cluster masses are quite hard to measure, having only been measured so far for about ~1000 clusters with Gaia data – so I had to develop a lot of things to get this working nicely. This is done by summing photometric masses of member stars, applying some corrections, and fitting a mass function to the cluster.

All of the details are in the paper, but the take home message is that corrections I implemented for selection effects and unresolved binary stars are really important to get accurate masses! In fact, selection effect corrections have never been done for cluster masses in this way before, despite the fact that they make a big difference to final cluster mass measurements.

Does it work?

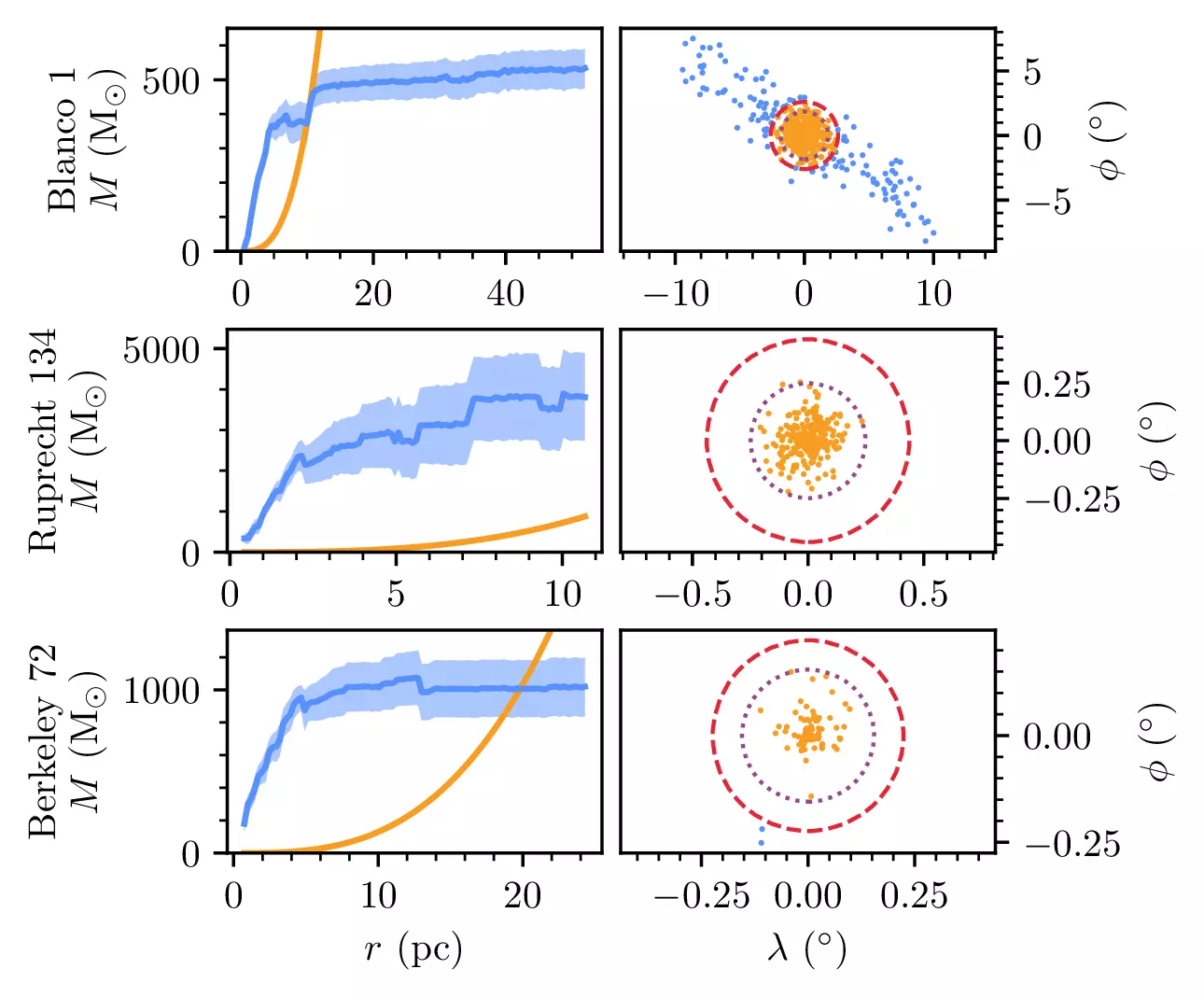

Yes! Clusters can be clearly divided now into those likely to be bound and those unlikely to be bound. Let’s look at the determination process for three reliable clusters first: they have ranges where their mass (blue line) is higher than the theoretical Jacobi mass (orange line), meaning that they are bound at that radius:

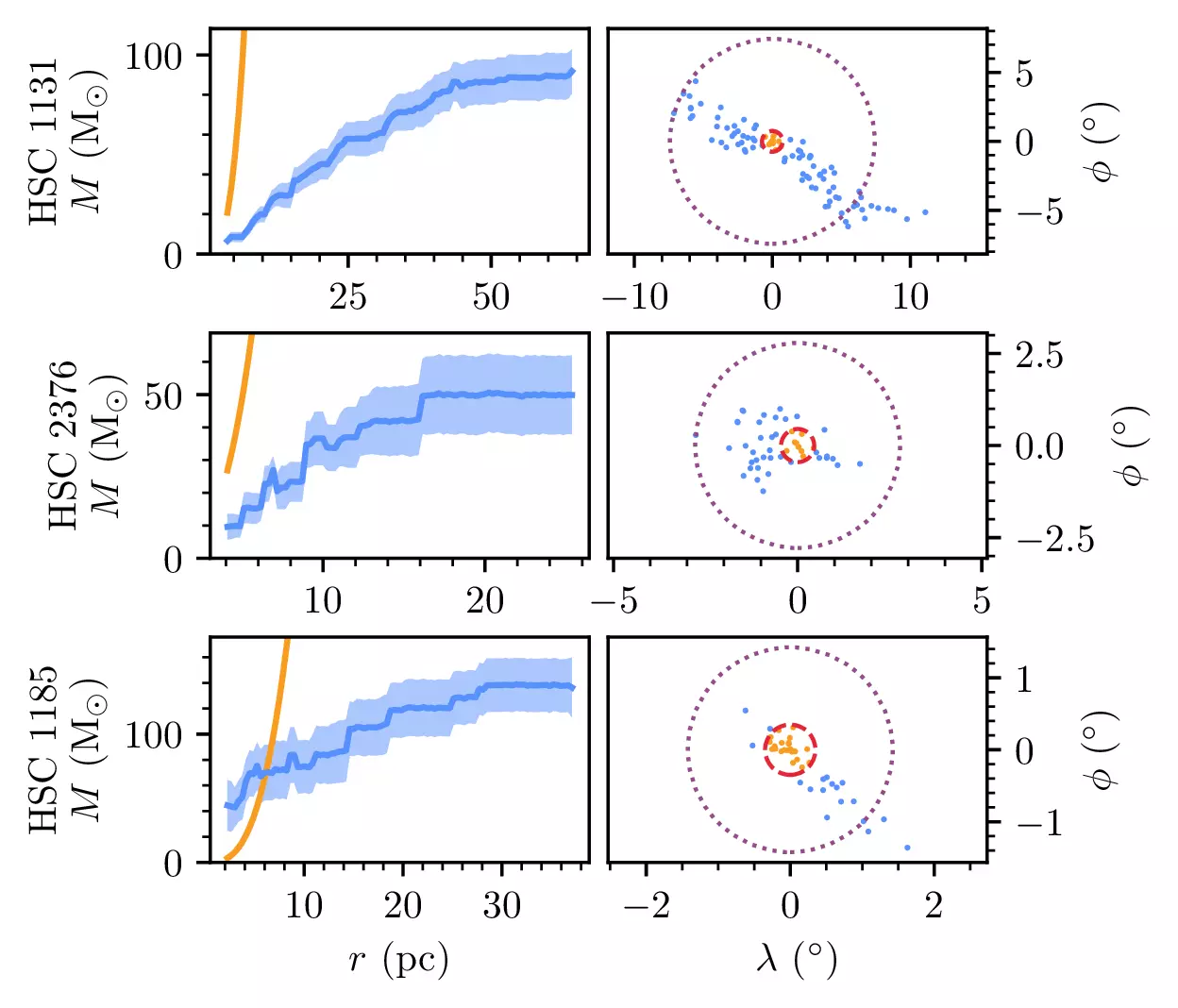

On the other hand, suspect clusters (like our disk stream from earlier) do not have a Jacobi radius:

And this also allows us to now confirm some new open clusters, like the ~65 solar mass HSC 1185!

The impact on the overall catalogue

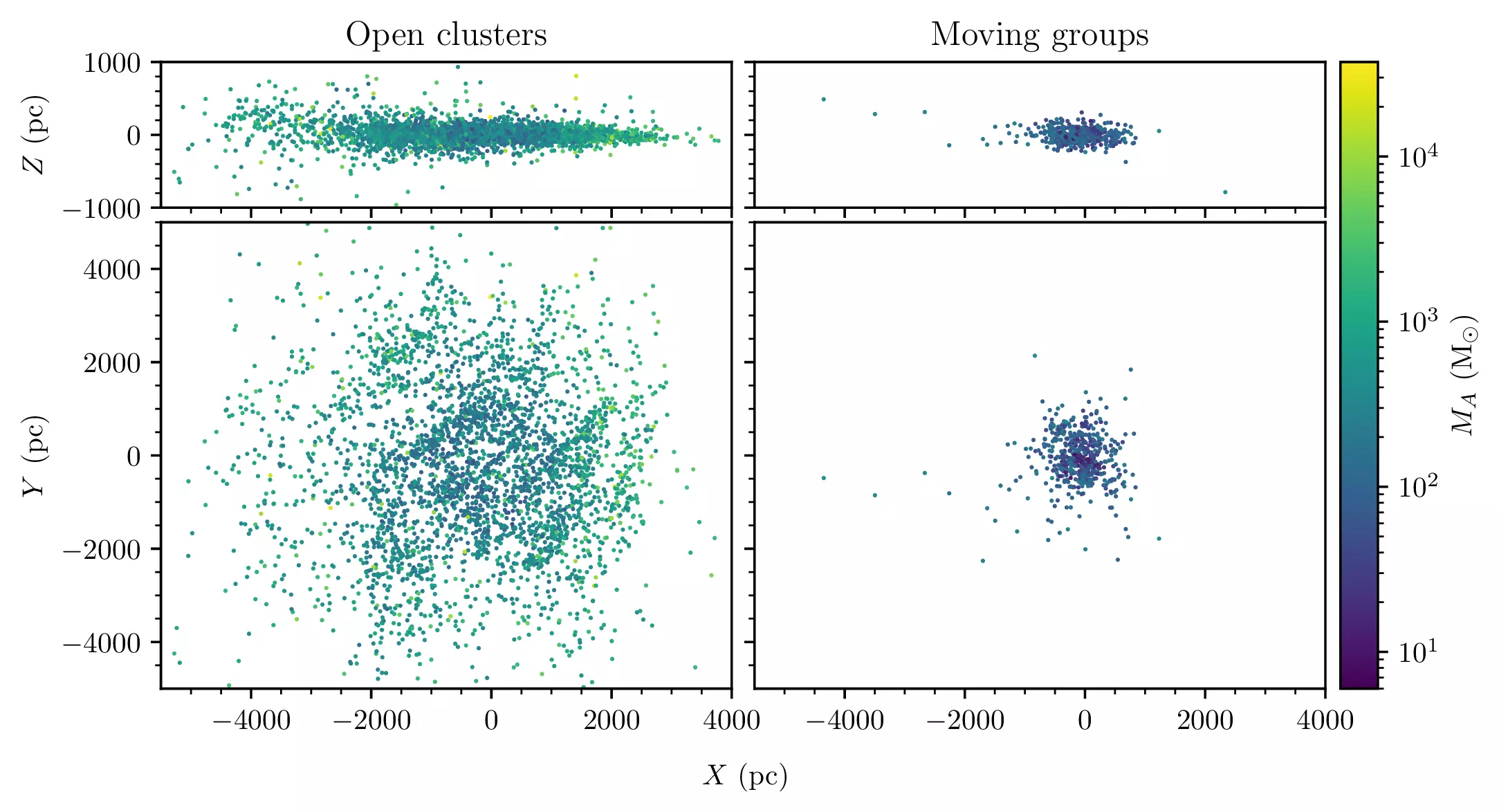

Next, I measured these parameters for 6957 clusters in our catalogue, making it possible to cut between bound clusters (open clusters) and unbound ones (moving groups):

Ta-da! As expected, we have an overdensity of unbound clusters near to the Sun, while open clusters have a ‘flat’ distribution in this range (as expected).

It’s really awesome to get this working! This new, more accurate way to classify resolved star clusters will be useful for many things in the future. And as a result of this work, we also publish the largest ever catalogue of Milky Way cluster masses and radii – a catalogue that reveals many interesting things about our galaxy.

Does this mean the unbound clusters can be thrown away now?

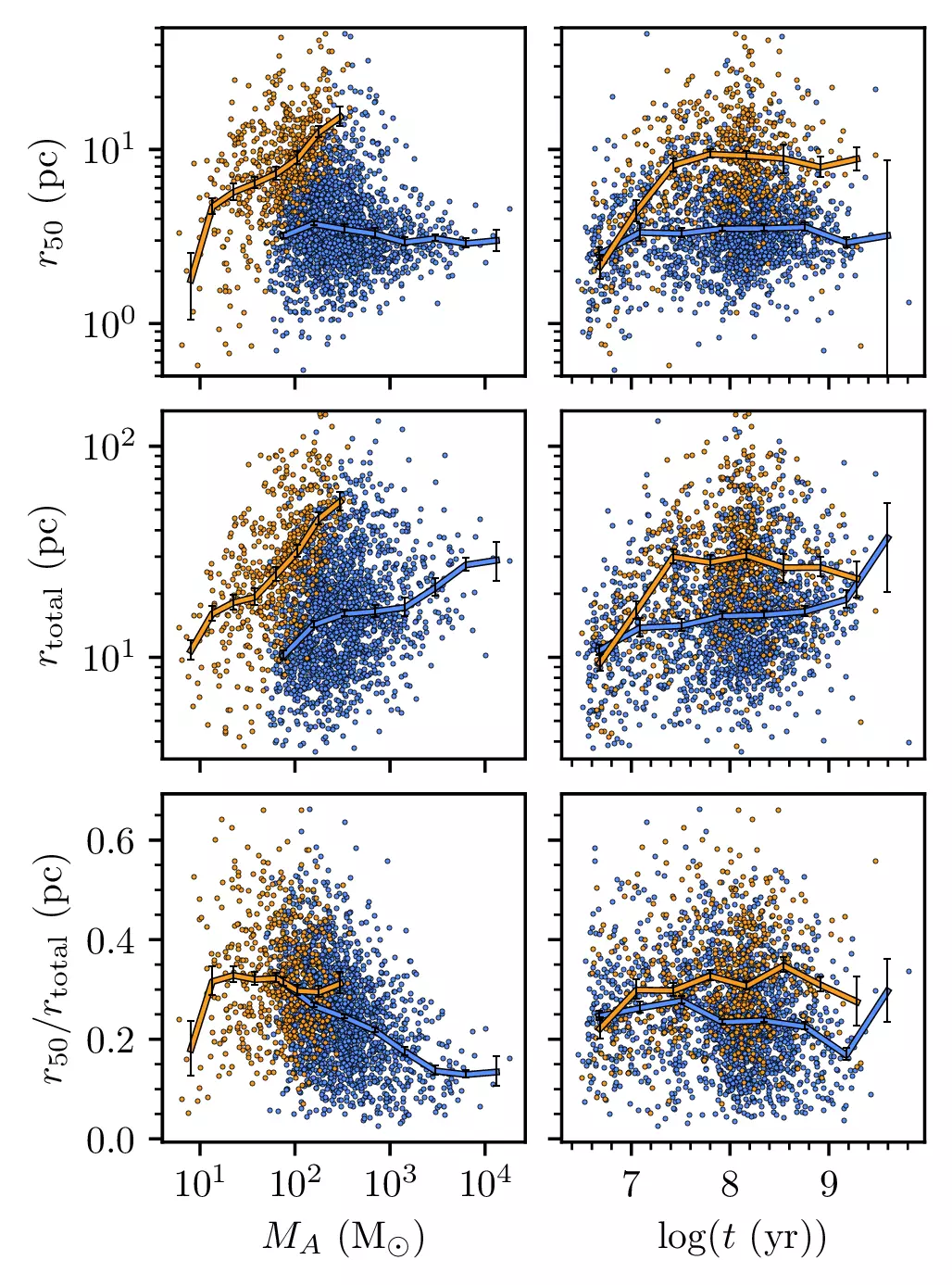

No! They’re still fascinating objects, and I think it’s amazing that one catalogue can be used to study both bound and unbound star formation remnants at the same time. For instance, they have different parameters:

With bound clusters (blue) and unbound ones (orange) clearly forming at the same size (top right plot), but with unbound clusters expanding while bound ones stay the same. It’s a goldmine of objects to study, where every cluster has all relevant parameters calculated for it!

Having this many masses is amazing

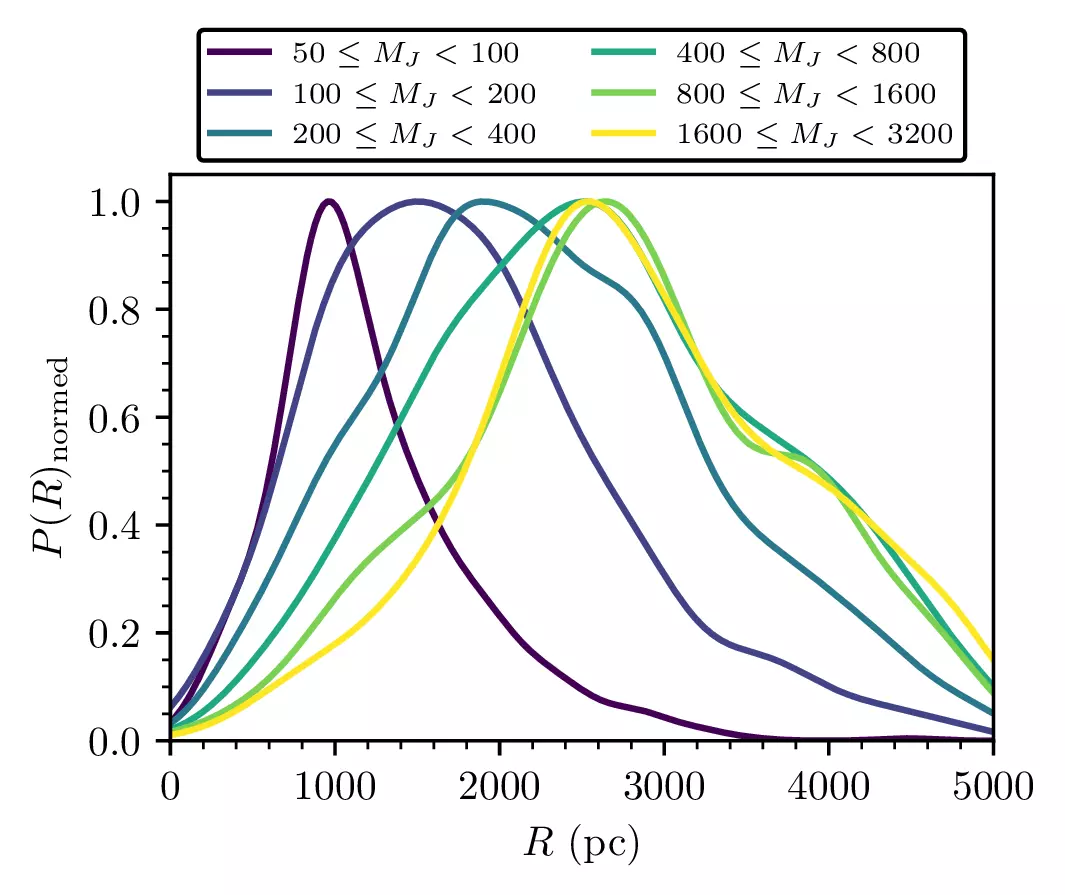

Never before have we had so many cluster masses! We noticed some very interesting trends. Firstly, the completeness of our catalogue depends clearly on cluster mass, shown here by plotting the 2D distance R = sqrt(X^2 + Y^2) distribution of clusters:

From this, we estimated that our catalogue is 100% complete dependent on a log-linear law up to 2.7 kpc, after which something else (such as extinction) becomes the dominant effect. A commonly refuted claim in the Gaia era is that the open cluster census is complete within 1.8 kpc, which we can quantify exactly: our catalogue is only complete within 1.8 kpc for clusters above 230 solar masses. That’s actually quite high – that’s about the same as the Hyades! More cluster discoveries within ~2 kpc of the Sun can definitely be expected in the coming years, using new data releases like Gaia DR4.

Using the completeness estimates to derive other things

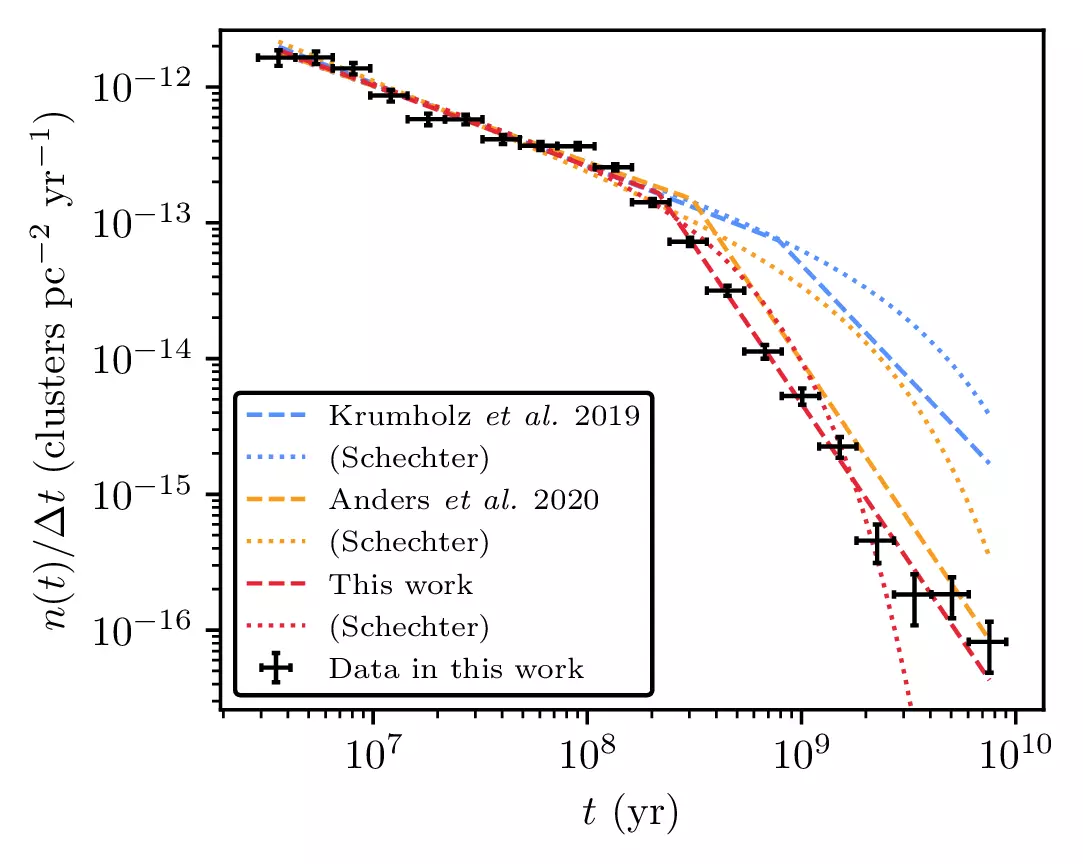

We were also able to derive an age function of the overall catalogue, finding good agreement with another Gaia work (Anders+2020):

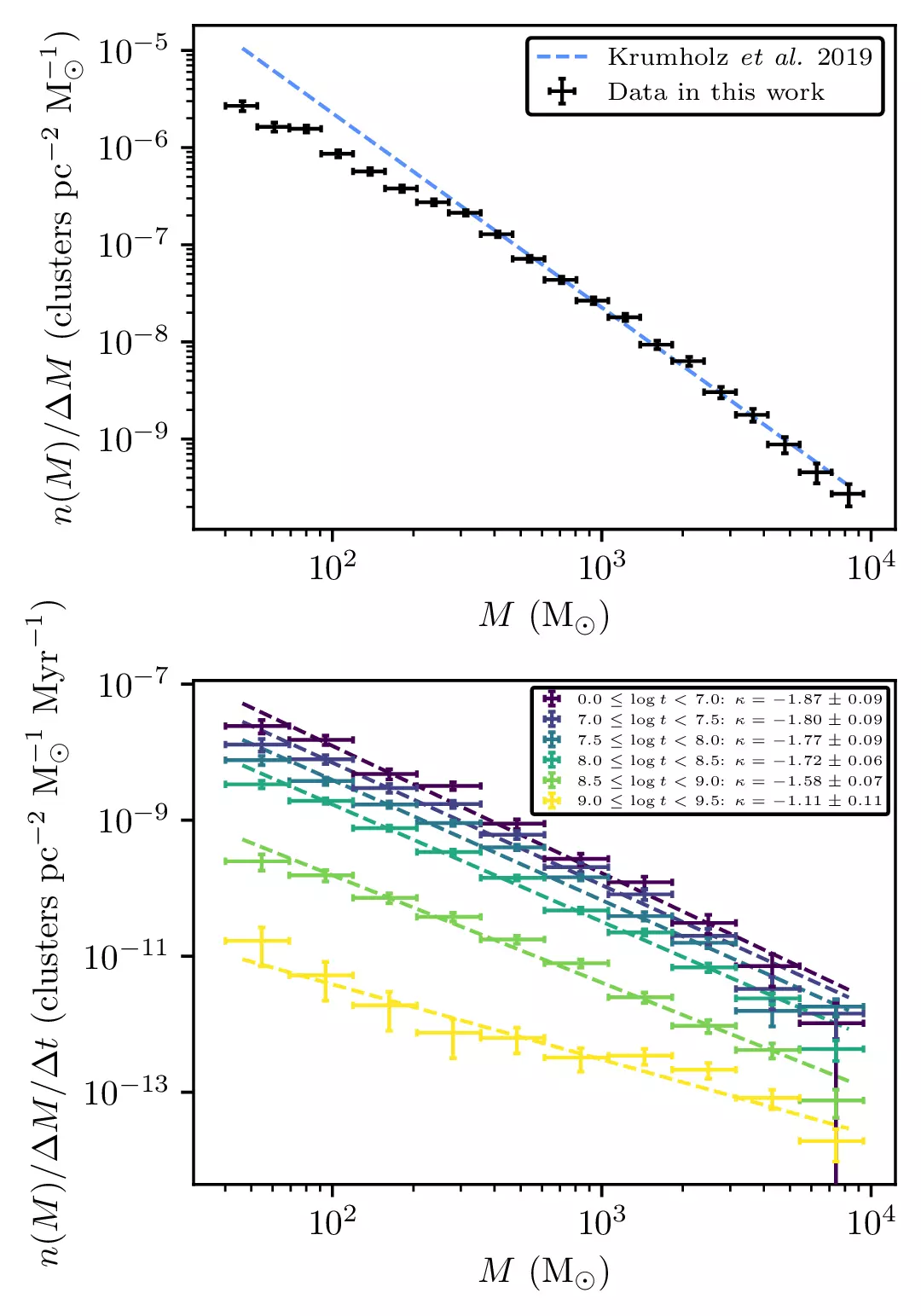

And we also derive the first ever Gaia-era global cluster mass function. We find that the global mass function is compatible with an index -2 power law at young ages, flattening over time. This suggests that low-mass clusters are destroyed faster than high-mass ones, and sets strong observational constraints on the rates of cluster formation and dissolution!

These constraints will be extremely useful to future theoretical works, as we derive how the population of open clusters changes as a function of age and mass.

A note on cluster mass functions

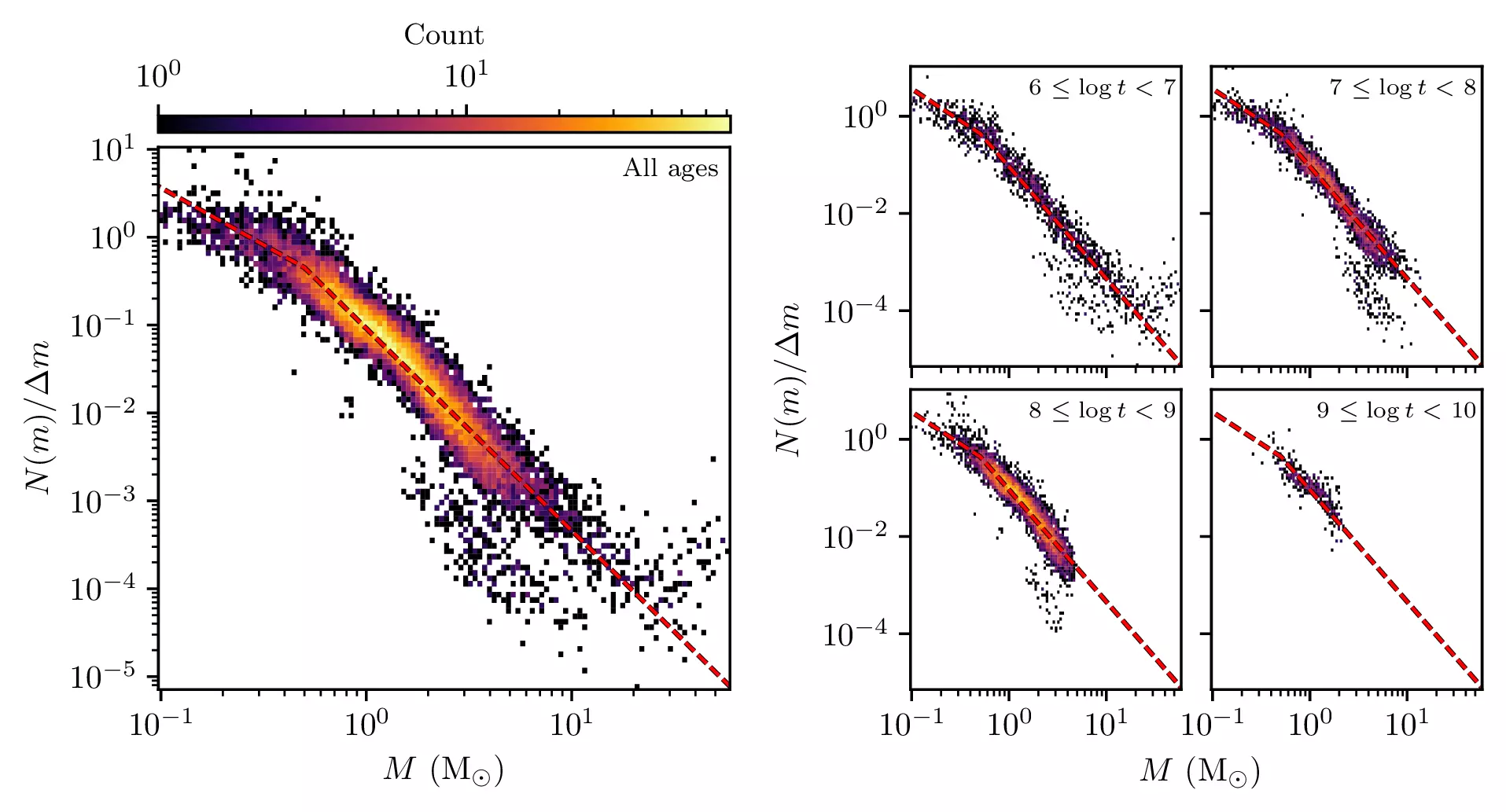

Finally, something interesting popped up with cluster mass functions: within some scatter, they’re all compatible with a Kroupa IMF! The below plot shows every cluster mass bin point on a 2D histogram, with the Kroupa IMF shown by the red dashed line:

It seems like the Milky Way’s open clusters (at least those in the solar neighbourhood) form with the same initial mass function, and that this IMF does not change much with time. We do see some evidence that cluster mass functions flatten at high ages. There are also some notable outliers on the plot above – for instance, we have too many high-mass stars in mass bins over 20 solar masses, likely due to very young clusters having over-estimated ages. There is also a “point cloud” below the bulk of cluster mass functions at masses between 2 and 10 solar masses, affecting about ~900 out of ~5600 open clusters. This is discussed at length in the paper: these outliers are likely due to many issues, including poor colour-magnitude diagrams, small number statistics, and poor isochrone fits (as these outliers are usually always at the tip of the main sequence of clusters.) None of the outliers qualitatively change total cluster masses, however, as they all have high uncertainties.

Other than that, everything is fit pretty well by a single broken power law IMF! This is significant because we cannot reproduce the results of other recent papers that have found that different open clusters have very different mass functions. This is probably due to selection effects that can artificially make cluster mass functions have different slopes if not corrected for.

In summary

This paper measures whether 6957 clusters are gravitationally bound, creating a star cluster catalogue that I’m really proud of that includes masses, radii, ages, individual stellar mass estimates, and more… you can read it now on the arXiv!